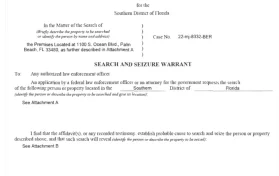

On Friday, the search warrant and property receipt related to the Trump raid at Mar-a-Lago was unsealed and revealed to the public. The warrant revealed three different possible U.S. codes that the FBI was investigating in order to obtain the search warrant. One of those happened to be a 1917 law named the Espionage Act.

So, what is this piece of legislation? The legislation was enacted in June 1917, a mere two months after the United States entered into the first world war. It’s noteworthy to know that as soon as WWI ended in 1918, numerous lawsuits regarding the First Amendment came before the nation’s courts. These suits would bring about landmark rulings regarding freedoms protected by the Constitution.

The First Amendment Encyclopedia offers an explanation of the Espionage Act as it was written at the time: “(The Act) prohibited obtaining information, recording pictures, or copying descriptions of any information relating to the national defense with intent or reason to believe that the information may be used for the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation.”

The act also provided penalties for anyone who attempted to obstruct enlistment in the U.S. military. Charles Schenck, a Socialist, created and distributed fliers decrying the draft (conscription); the Supreme Court upheld his conviction as this was a part of the Espionage Act. The Court ruled that the Espionage Act convictions of Schenck and others (including declaring up to 74 newspapers across the country as “nonmailable”) was acceptable as the U.S. was in a time of war and the Executive was within the rights of the law.

Interestingly enough, a poet many Americans studied in high school English, Oliver Wendell Holmes, wrote missives claiming that the Espionage Act infringed upon First Amendment rights.

In 1918, Congress passed the Sedition Act, which dealt with limiting speech critical of WWI. The Sedition Act would eventually be repealed, but portions of the Espionage Act are still on the books today.

Edward Snowden was charged with violated the Espionage Act when he allegedly leaked classified documents to The Guardian. Two lobbyists for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee were charged with a violation of the act in 2006, but three years later, the charges were dropped. Julian Assange has been charged with 17 violations of the act, chiefly publication of documents.

Now, the government is investigating former President Donald Trump after materials he says are declassified were boxed up by the GSA (a government agency) and shipped to his home in Palm Beach, Florida.

According to a former DOJ lawyer, Robert Driscoll, President Trump could be charged under the Espionage Act “because the Espionage Act was passed before the classification system (of government documents) was developed.” The legislation refers to “National Defense” information, but even then, the declassification of said documents might not prevent a charge under the Espionage Act: “(classification status of documents) is not a defense to an espionage charge that the information may have already been declassified.”

For instance, The Washington Post reported on Thursday that the DOJ was looking for documents related to nuclear weapons. By that token, if Trump had knowingly taken those documents, and they could hurt the U.S. if they were ever to make their way to foreign adversaries, then the Espionage Act charge is plausible.

A Trump attorney says that if these documents belonged to the president and he had already declassified them, then he was free to take them where he wished.

Even the former DOJ attorney conceded: “The Espionage Act most commonly is used for reporters who have leaked information or been the recipients of leaked info.

A release of the affidavit presented to Judge Bruce Reinhart would clear up a lot of those questions – it would provide transparency about what the documents were, why they are sensitive, and why they were taken to Mar-a-Lago. However, Driscoll said that affidavit probably wouldn’t be available to the public for a long time.